Module 5: Assessing Risk

Module Created by Dr. Krystal Simmons

Content

Definitions:

Crisis (Kanel, 2015)

-

-

- Precipitating event

- Perception as threatening or damaging

- Emotional distress

- Impairment in functioning

- Failure to use coping methods

-

Crisis State

-

-

- One’s response to a crisis event and perception of their ability to cope with the crisis event.

-

Crisis State Response

-

-

- Parasuicide: Deliberate self-injury or imminent risk of death, with or without the intent to die (Gunnell & Frankel, 1994)

-

Suicide Attempts

Nonsuicidal Self-Injury (NSSI)

Suicide (CDC, 2021)

-

-

- The act of intentionally taking one’s life causing death (also referred to as suicide completion).

-

Suicidal behavior

-

-

- A broad term describing those who engage in the thoughts of suicide intent (suicidal ideation) or the deliberate act to harm oneself with an imminent risk of death (suicide attempt).

-

Overview of Crisis Intervention

According to the CDC (2021), suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States, the second leading cause of death for individuals ages 10-34, and rates have increased by 33% between 1999-2019. Corresponding to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, emergency department visits among adolescents increased by 31% in 2020 compared to the same period for mental-health related concerns (Yard et al., 2021).

When assessing for risk, consider 4 things:

-

-

- Asses for “intention” to distinguish between suicide risk (intention to end one’s life) and nonsuicidal self-injury (intention to relieve emotional pain and distress) (Holland et al., 2021)

- According to Chu & Weaver (2020), the goal of risk assessment is to identify not intervene (Sensitivity vs. Specificity), study your standards of practice and consult, consult, consult! (i.e., seek supervision!)

- You assess signs and symptoms in every session. Incorporate all information to inform results. Know the law and your ethical obligations (e.g., Duty to warn per your state). Follow-up!

- Document, document, document! Then seek supervision again.

-

Importance of crisis readiness and gatekeeper training benefits (Mo, Ko, and Xin, 2018):

Knowledge: Increased declarative and self-perceived knowledge

Self-efficacy: Increased self-efficacy for identifying and responding to suicidal individuals after training

Gatekeeper Skills: Increased communication and dealing with self-harm skills

Intervention: Increased likelihood to intervene

Attitude: Increased attitudes regarding acceptance and prevention of adolescent suicide

Behavior: Increased gatekeeper behavior (asking about suicide)

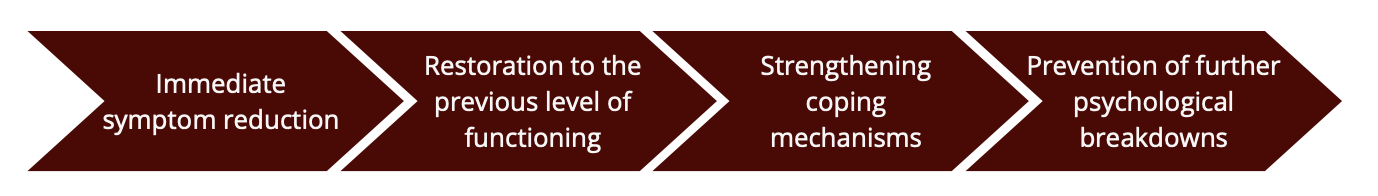

Goals of Crisis Intervention

Assessing Risk

It is critical to consider safety on a telehealth platform and understand how it is different from in-person interventions. When in person, if your client is presenting with and reporting suicidal ideation, there are hands-on approaches for engagement, such as ensuring comfort (e.g., handing over a tissue if crying) and safety (visually monitoring a client until in a safe place). The therapist is able to confirm that a client leaves the therapy room safely and if a hospital/inpatient referral is needed, they can coordinate and be present during transportation. Via telehealth, these safeguards are limited. Therefore, it is important to consider the following action steps:

- Know the laws in your state for mental health intervention. Identify the ethics and policies related to crisis intervention for your agency and licensing board.

- Identify local community health resources that a client can be referred out or transported to if in crisis. This may include obtaining the contact information of local law enforcement.

- Note: Consider who you need to call, why, and predict potential outcomes that may impact your client due to their background (e.g., race, ethnicity, SES). If you need to involve law enforcement during a crisis event that is solely mental-health related (as opposed to a physical threat), call the agency and clearly state that it is a ”mental health” emergency to help the operator dispatch personnel with training in mental health crisis intervention, such as the Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT). This option may not be available in all locations, so be sure to research and establish contacts with your law enforcement agencies in advance.

- Obtain the location and address of your client during the first contact and document. The first contact may be during the phone screening or the intake session, this depends on your training

- Verify client’s call back phone number should videoconferencing encounter technical difficulties and the remainder of the session needs to be completed via phone.g site’s procedures.

- Confirm your client’s location at each session and document this safety check. If your client is in the state, but at another location, work with your supervisor on a safety plan prior to starting the session in case emergency personnel need to be dispatched to a location where you are unfamiliar with the local resources. If your client is out of state, check with your supervisor and state laws to determine if the client can be seen across state lines. In most cases, the answer is no.

- Identify an emergency contact (or multiple contacts) with your client prior to conducting psychological services. If your client is in crisis, has a health emergency, or is unresponsive, who can you contact to help your client? On their chart, document the name and number of the emergency contact(s) and the confirmation that your client consented to call this person in an emergency situation. For child clients, the guardian is often the emergency contact. If your client refuses to provide an emergency contact, describe what the alternative options will be (e.g., calling the local police department or ambulance) and document their refusal.

- Have trauma screening tools (e.g., risk assessment checklist, safety plans, notification of emergency conference form), crisis intervention referral forms, and contact information for community resources readily available to you while you are in a telehealth session.

- Training sites should have a standard operating procedure that clearly states how to respond to crisis situations, how to document, and who to seek supervision from during the intervention (e.g., training/clinic director vs. site supervisor). Review and update these protocols routinely

- Routinely update safety protocols for your agency and the contact information for your community resources.

Precipitating Factors

Obtaining a good history is important to understanding potential risks and recognizing risk factors as they develop. Those who have a history or are susceptible to vulnerabilities such as recent trauma, significant losses (e.g., job loss, death of a loved one), persistent rejection, stressful life event, shame/dishonor, or social discord depressive and anxious symptoms, trauma, difficult

Risk Factors

- Previous attempts

- Prior suicide attempt is the strongest risk factor for completed suicide in adults, increasing the risk between 10-60 fold (Bridge, Goldstein, & Brent, 2006)

- 15–30% of adolescents who attempt suicide attempt again within a one year periodThe most at-risk period is in the first 3-6 months after an attempt

- The most at-risk period is in the first 3-6 months after an attempt

- Mental health history, especially depression and anxiety

- Abuse history, especially among youth

- Dating violence and victimization, especially among females

- History of violent behavior and substance use

- Those with more frequent substance combined with violent behaviors have significantly more attempts (Pena, Matthieu, Zayas, Masyn, & Caine, 2012)

- Less participation in religious activity

- Predicted more acceptance of suicide and more suicide planning

- Acceptability of suicide

- “Young persons with the greatest acceptance of suicide were more than fourteen times more likely to plan their suicide as those with the least acceptance of suicide (26.3% versus 1.8%)” (Joe, Romer, & Jamieson, 2007, p. 171)

- Lack of future plans/hopelessness

- “Persons who had experienced hopelessness symptoms, including feeling sad unable to carry out normal functions, were more likely to report suicide plans” (Joe et al., 2007, p. 170)

- Did not eliminate the relationship between acceptance and planning

Warning Signs

Feelings of depression, hopelessness, thwarted belonging, and perceived burdensomeness are signs of suicidal ideation. Consider inquiring about these feelings, defining the feeling, and scaling feelings during assessments.

- Guilt, shame, self-hatred – “What I did was unforgivable”

- Pervasive sadness

- Persistent anxiety

- Persistent agitation

- Persistent, uncharacteristic anger, hostility, or irritability

- Confusion – can’t think

Person may talk about suicide directly or indirectly, make social media posts, journal about feelings, or make implications in other writings (e.g., school essay). Take statements seriously in consideration of data obtained through the risk assessment.

- Hopeless

- “Things will never get better”

- “There’s no point in trying;” can’t see a future

- Helpless

- “There’s nothing I can do about it

- ”I can’t do anything right.”

- Worthless

- “Everyone would be better off without me”

- “I’m not worth your effort.”

Observations and reports of uncharacteristic behavioral changes is key to a comprehensive risk assessment. Acknowledging the signs of risk can be the entry to asking questions about potential ideation and crisis states.

- Plans-Give away prized possessions, making final arrangements-putting affairs (e.g., finances) in order.

- Personality-more withdrawn, low energy, apathetic, or more boisterous, talkative, outgoing.

- Behavioral Risks

- Loss of interest in personal appearance, hygiene, neatness of personal items, space

- Uncharacteristic aggression, bullying behavior

- History of discipline problems

- Loss of interest in hobbies and work

- Marked decrease in work performance

- Sleep, appetite increase or decrease

- Prolong negative attitude

- Becoming accident-prone

- Sublethal gestures or attempts (e.g., overdose, wrist cutting).

-

- Have trauma screening tools (e.g., risk assessment checklist, safety plans, notification of emergency conference form), crisis intervention referral forms, and contact information for community resources readily available to you while you are in a telehealth session.

- Training sites should have a standard operating procedure that clearly states how to respond to crisis situations, how to document, and who to seek supervision from during the intervention (e.g., training/clinic director vs. site supervisor). Review and update these protocols routinely

- Routinely update safety protocols for your agency and the contact information for your community resources.

Protective Factors

Protective factors: In addition to assessing for risk, it is important to acknowledge positive aspects of people’s coping, support systems, behaviors, and related factors. Protective factors can serve as a buffer to suicidal behaviors; the more protective factors a person possesses, there is potential for that person to be less likely to engage in suicidal behaviors.

- Race/culture – Some cultures among racial groups (e.g., Black and African Americans) identify suicide as a taboo and many are discouraged from engaging in suicidal behaviors, decreasing risk. However, the risk may still exist and some may engage in suicidal behaviors by proxy (e.g., engage in violent/life-threatening activities, suicide by cop, etc.)

- Religion

- Family cohesion

- Sense of connectedness

- Emotional well-being

- Sense of purpose

- Hope

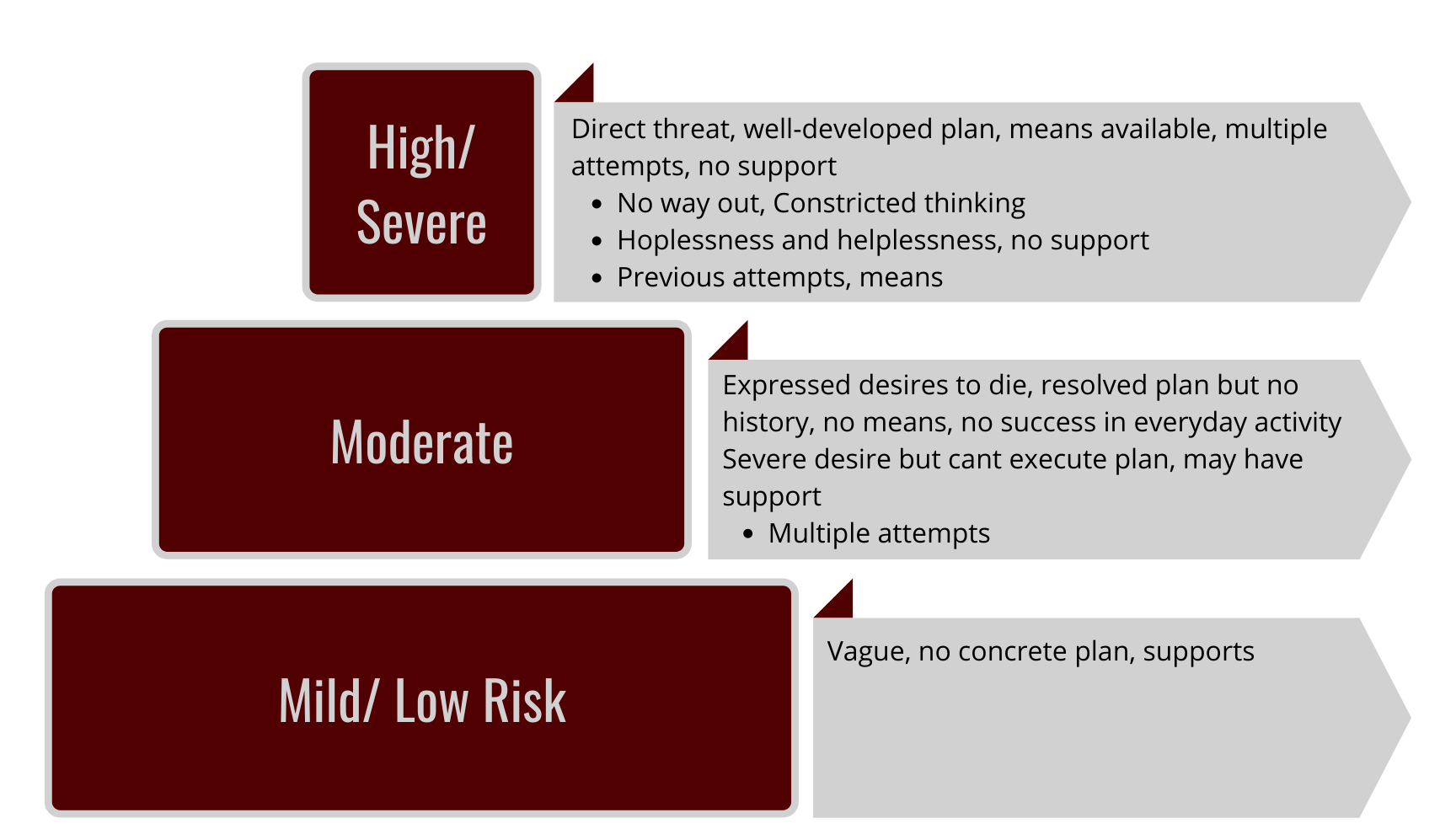

Strategies for Direct Inquiry & Determining Level of Risk

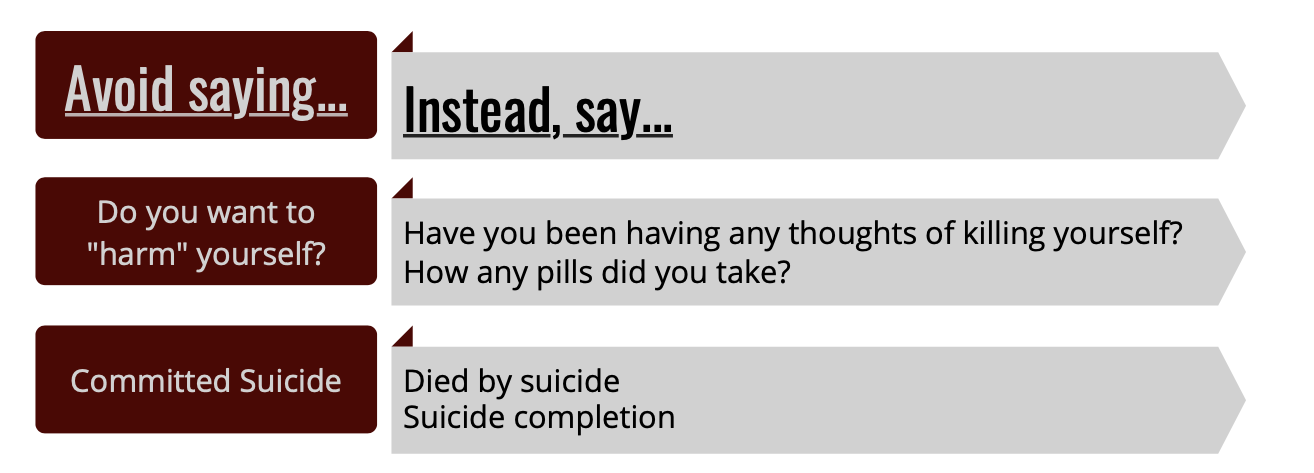

It is important to be aware of the language used in a risk assessment. Being clear and direct, while being culturally responsive, is key; many will have to practice when asking about one’s intent to kill themselves. Normalizing, validating experiences, clarifying (asking for specific facts, thoughts, and behaviors), and making gentle assumptions are strategies for engaging in direct inquiry (Shea, 2012 as referenced by Chu & Weaver, 2020).

Joiner’s (2005) interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior is a common approach to conceptualizing the level of risk. The interpersonal theory of suicide postulates that suicidal ideation is directly related to high levels of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. Perceived burdensomeness is the perception of a lack of social connectedness and the notion that by ending one’s life, others would be “better off”. As social beings, the feelings of thwarted belongingness contribute to a sense of loneliness and isolation. Mediated by feelings of hopelessness, those with feelings elevated perceived burdensomeness, low sense of belongingness will have increased suicidal desire. Joiner’s third factor is the capability for suicide, known as the acquired ability for suicide in earlier models. Those capable of suicide experienced repeated exposure to painful behaviors and/or life-threatening events, along with possible genetic predispositions makes the threat of death less fear-provoking. Risk of suicide increases when all factors are present and there is a history of previous attempts.

Indicators of Risk (Joiner 2005, 2011)

*Note that previous attempts is not as strong of a predictor of suicidal behaviors for children/adolescents as it is for adults.

Safety Planning and Intervention

There is no empirical support for the efficacy in using documentation commonly referred to as “no-harm” contracts (Stanley & Brown, 2012). However, we do support the use of safety plans and coping cards, which tells people what to do instead of what not to do (Garvey et al. 2009; Joiner, 2011) Safety planning is a collaborative process and an opportunity to document triggers, coping mechanisms, and how and who to access for support. These documents include hotlines and accessible resources. Safety plans are also an opportunity for further assessment to determine whether a client can conceptualize and identify positive coping strategies and who do they list as perceived support systems if any are listed. If none are listed, or the client refuses to complete a safety plan, these factors may indicate a higher risk of suicide.

Your supervisor should guide you on the appropriate intervention approaches and treatment plan for your client while they are in crisis, immediately after the crisis event, and long-term care. Interventions shown to be most efficacious for those with suicidal ideation behaviors are cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies for youth and adults (Glenn et al., 2019; Brown and Jager-Hyman, 2014). Involving family and caregivers in the treatment of adults and youth with suicidal ideation and behaviors is also helpful (Brown and Jager-Hyman, 2014; Glenn et al., 2019; Holland et al., 2021). Consider virtual tools and telephone resources as part of the intervention. These tools can help with mood tracking, progress monitoring, and encouraging positive connections between peer support systems if unavailable in person:

- A Friend Asks

- Better Stop Suicide

- Crisis Care (specific to youth)

- mHealth

- Moodkit

- Prevensuic (app in Spanish)

- ReliefLink (specific to youth)

- Suicide or Survive

- Suicide Preventive (for practitioners)

- Suicide Lifeguard

- Virtual Hope Box (supports multiple languages)

If you or someone you know is experiencing a crisis, there are resources available:

- Inform your mental health provider

- You can call the suicide prevention 24/7 hotline: 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

- You can chat with someone at https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/chat/

- Text HOME to 741741

Resources

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention-Supporting Diverse Communities: https://afsp.org/supporting-diverse-communities

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2021). Preventing Suicide Fact Sheet: https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/pdf/preventing-suicide-factsheet-2021-508.pdf

- Lifeline: https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center: https://www.sprc.org/

- The Trevor Project: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/

- Youth.gov: https://youth.gov/youth-topics/youth-suicide-prevention

Video

The following presentation will show an example of a risk assessment on a client in a teletherapy session.

Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2021). Preventing Suicide Fact Sheet: https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/pdf/preventing-suicide-factsheet-2021-508.pdf

- Yard, Ellen, et al. “Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12–25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January 2019–May 2021.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 70.24 (2021): 888.